Post written by Birgit Pepin, 4TU.CEE leader of TU Eindhoven

“To navigate through such uncertainty, students will need to develop curiosity, imagination, resilience and self-regulation; they will need to respect and appreciate the ideas, perspectives and values of others; and they will need to cope with failure and rejection, and to move forward in the face of adversity. Their motivation will be more than getting a good job and a high income; they will also need to care about the well-being of their friends and families, their communities and the planet.”

Position paper OECD and engineering education

If you think that the above quote comes from our recent university documents, you are mistaken. It is from the OECD document “The future of education and skills- education 2030- the future we want” – a position paper by the OECD (based on first investigations of their project). If you think that this paper relates to higher education, you are mistaken – it is meant for education from pre-school to higher education!

If you think that the above quote comes from our recent university documents, you are mistaken. It is from the OECD document “The future of education and skills- education 2030- the future we want” – a position paper by the OECD (based on first investigations of their project). If you think that this paper relates to higher education, you are mistaken – it is meant for education from pre-school to higher education!

In this blog I summarize the document (which I recently read) by highlighting some of the thoughts that I found most valuable for us in engineering education, and with the view to the “engineer of the future” and engineering education 2030.

In the foreword the director of the ‘The Future of Education and Skills 2030’ project, Andreas Schleicher, outlines the underpinning questions of the project:

- What knowledge, skills, attitudes and values will today’s students need to thrive and shape their world?

- How can instructional systems develop these knowledge, skills, attitudes and values effectively?

How to deal with future challenges

The background to the project is that, so he claims, we are facing “unprecedented challenges” -social, economic and environmental – and problems and uncertainties that we cannot anticipate, “it will be a shared responsibility to seize opportunities and find solutions”. He predicts that in order to “navigate through such uncertainty, students will need to develop curiosity, imagination, resilience and self- regulation. They will need to respect and appreciate the ideas, perspectives and values of others. And they will need to cope with failure and rejection, and to move forward in the face of adversity.

Moreover, he is certain that their motivation (for education) will be “more than getting a good job and a high income”, but they will also need to think about, and care for “the well-being of their friends and families, their communities and the planet”. In order to reach these aims, he states, “education can equip learners with agency and a sense of purpose, and the competencies they need, to shape their own lives and contribute to the lives of others”. In short, and translating these aims to engineering education, we (as engineering educators) have to help our students to become “active, responsible, and engaged citizens” as engineers.

Learner agency and co-agency

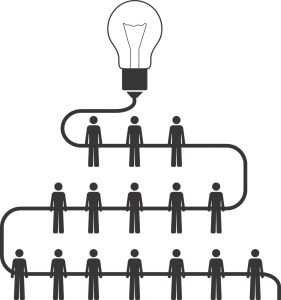

Attending in more detail to his vision, key features are (1) “learner agency”, and (2) “co-agency”. With reference to (2) he explains “co-agency” as “the interactive, mutually supportive relationships that help learners to progress towards their valued goals”. In such a context there are no instructors on the one hand, and learners on the other, but everyone should be considered a learner: students, teachers, school managers, parents and communities. Concerning (1) learner agency, in his opinion there are two factors in particular that help learners enable agency: (a) a “personalised learning environment that supports and motivates each student to nurture his or her passions, make connections between different learning experiences and opportunities, and design their own learning projects and processes in collaboration with others”; and (b) a solid knowledge foundation where “literacy and numeracy remain crucial”. In terms of literacies he emphasizes that “digital literacy” and “data literacy” are becoming increasingly essential.

Innovation through co-operation and collaboration

What caught my attention most were his elaborations on knowledge and competence development. He predicts that “disciplinary knowledge will continue to be important. It is the raw material from which new knowledge is developed, together with the capacity to think across the boundaries of disciplines and “connect the dots”.

What caught my attention most were his elaborations on knowledge and competence development. He predicts that “disciplinary knowledge will continue to be important. It is the raw material from which new knowledge is developed, together with the capacity to think across the boundaries of disciplines and “connect the dots”.

Interestingly, he divides knowledge into:

- epistemic knowledge (knowledge about the disciplines), e.g. knowing how to think like a mathematician, historian or scientist. It enables students to extend their disciplinary knowledge and is conditional for lifelong learning;

- procedural knowledge, which he assumes can be acquired through “practical problem-solving, such as through design thinking and systems thinking”.

Of course, students will be expected to apply their knowledge in “unknown and evolving circumstances”, for which “they will need a broad range of skills, including cognitive and meta-cognitive skills (e.g. critical thinking, creative thinking, learning to learn and self-regulation); social and emotional skills (e.g. empathy, self-efficacy and collaboration); and practical and physical skills (e.g. using new information and communication technology devices)”. In terms of innovation, he presumes that “innovation springs not from individuals thinking and working alone, but through co-operation and collaboration with others to draw on existing knowledge to create new knowledge. The constructs that underpin the competency include adaptability, creativity, curiosity and open-mindedness”.

Systems thinking

He sums up that in order to be prepared for the future, “individuals have to learn to think and act in a more holistic way, taking into account the interconnections and interrelations between contradictory or incompatible ideas, logic and positions, from both short- and long-term perspectives. In other words, they have to learn to be systems thinkers”.

This speaks to all of us in STEM education, definitely to me (as a mathematics educator), as I have always thought of ‘developing an understanding of a concept’ means ‘making connections’ (or as he put it earlier “connecting the dots”). And it is through the richness (or paucity) of connections that we can evaluate whether we have deeply understood, or developed a surface understanding of the concept. Which kinds of connections to make, which ones are likely to be most helpful, and how to support the making or scaffolding of connections, is surely the task of the teacher. ‘Making connections’ (as a teacher) also includes connecting to our students, their thinking, their experiences, and their interests, to name but a few.

Making dreams come true

Coming back to the initial quote, this outline is for the whole of education, and it emphasizes a broad personal development, which in addition to connected knowledge are also ideals in our engineering education. At the same time we know how difficult this is to make dreams come true, also in education. If we want to make a contribution in higher education, do we subscribe to these ideals, and how can we (start to) operationalise them?

This post has been written by my colleague Birgit Pepin, 4TU.CEE leader of TU Eindhoven, and was published on the weblog of 4TU.CEE (4tucee.weblog.tudelft.nl) March 20th, 2018.

This post has been written by my colleague Birgit Pepin, 4TU.CEE leader of TU Eindhoven, and was published on the weblog of 4TU.CEE (4tucee.weblog.tudelft.nl) March 20th, 2018.

The post and the OECD report are very much in line with my thinking about the necessary changes in engineering education, as you can read in the posts of my blog and my book.