My one but previous post was about the confluence of talent development, discovery and innovation at Skoltech, using the CDIO framework. At that same gathering the 4TU.Centre for Engineering Education took the opportunity to run workshops about topics that really matter: developing a career framework for academics who have an accent on education, and training students about the innovation of products when the technology that is needed has not yet reached the threshold of readiness for industrial application. Last but not least I delivered the workshop “Who does the CDIO Community want to be in 2030”. A video recorded impression of this workshop is available here.

Engineering knowledge innovation

Frido Smulders of TU Delft provoked the attendees by stating that almost all engineering curricula focus on design, engineering and research, while it is innovation that is on the highest agendas in engineering business. In education we forget to pay attention to what technological innovation is and how that unfolds over time in real-life engineering projects. It’s a serious deficiency, because almost all engineering graduates find their natural habitat in innovation. The reason for this deficiency, he said, is that no complete body of knowledge exists that is grounded on research of technological innovation practice.

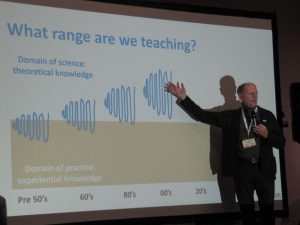

Frido Smulders, puzzling the audience how to teach the rapidly increasing amount of theoretical and experiential knowledge (private photo)

Single-loop and double-loop innovation

Students learn to develop new products, processes and systems using “old” validated technological knowledge. Or they generate new knowledge or transform fundamental knowledge into applied knowledge by doing research. Smulders terms that as “single-loop” innovation. But students donot learn how to develop technology that has not yet reached the required level of maturity but is needed to develop and build an innovative product or process. In that sense, the CDIO framework, he said, is not equipped for this smaller class of so-called “double-loop” innovations. He illustrated the deficiency with the first planes that used composite materials. These were designed by aeronautical engineers who still “thought in metals” and applied their old knowledge and practical experience to the use of carbon materials. It led to the ”black aluminium” parts that were adequate and safe but far from optimal.

Teaching technology innovation?

Engineers are responsible for designing innovative products, and also developing new technological knowledge. So where do we teach it? How do we find a balance between the growing amounts of scientific theories and engineering practice? Should not this also be contained in the CDIO framework? How should we teach the students to learn about the process of technology innovation?

Smulders brought the idea forward to bring examples of technology innovations into the classroom that have gone through many iterative cycles of trial and error in science and engineering practice, with the involvement of both engineering and social disciplines. His message was to complement engineering classes and design and research projects with an explicit mindset of continuous discovery, of success, failure and iteration. With a narrative of technological innovation that spans the full range of what happened, yet is generic enough to transfer to technological innovation processes in general. Paying explicit attention to what engineers experienced, assumed, predicted, tested, bread-boarded, forgot or overlooked, and how they combatted the frustration, hesitation and resistance to change on the shop floor. Such storylines would enable the students to develop planning scenarios for the development of new engineering knowledge that is urgently needed for modeling, simulating, analysing or manufacturing new products and systems that are already on the drawing table or are being engineered. Where anticipating risk and conscious risk taking is extremely important. His slides were food for thought for many, see also the video-recording.

Asked why the CDIO-way of thinking is so important for the future of engineering education, Smulders said: “These days, there’s so much more knowledge about engineering available in the scientific domain as well as in the domain of practice. At this point, we tend to teach as much as we know, but with the passage of time, we have come to know too much to teach, so basically we have to revert to another system that helps students to learn the basics, but also learn how to specialise later on in their career, and embark on a road of lifelong learning.”

University career frameworks

Jan van der Veen (University Twente) and Birgit Pepin (TU Eindhoven), both affiliated with the 4TU.Centre for Engineering Education, ran a workshop together with Clement Fortin (Skoltech) on university career frameworks that balance teaching performance and research achievement. A video recording of the session is available here. The framework is related to the progress of an international working group of 12 universities from all over the world, coordinated by the Royal Academy of Engineering project and chaired by Ruth Graham (see website).

In many universities management and staff wish to restore the balance between education and research in appraisal cycles and career paths, but few see how this can be achieved. The main problem is, Van der Veen said in his introduction, that most people who have to evaluate or approve professorships in education, are experts in disciplinary research themselves, don’t understand or appreciate education as such to the same level, and thus operate in a slow-death mode.

In many universities management and staff wish to restore the balance between education and research in appraisal cycles and career paths, but few see how this can be achieved. The main problem is, Van der Veen said in his introduction, that most people who have to evaluate or approve professorships in education, are experts in disciplinary research themselves, don’t understand or appreciate education as such to the same level, and thus operate in a slow-death mode.

Van der Veen showed University Twente’s ambitions. They aim at two professorships per Faculty with an emphasis on education. These have to be a national and international leader in teaching and learning (Level 4 of Ruth Graham’s Career Framework for University Teaching). The educational research they are doing has to be at associate professor level. Each Faculty shall also have leaders in teaching and learning, as well as scholarly teachers with senior university teaching qualification (Level 3). Thus innovation and research in teaching will really count in the promotion to Associate or Full Professorship. Also in the Tenure Track training programme more emphasis will be put on teaching performance. See also the UToday post1 and post2 (in Dutch).

Pepin of TU Eindhoven explained their system of Advanced University Teaching Innovation Qualification (AUTIQ), where achievements in educational innovation and research projects provide incentives for university teachers and count in career promotions. Their emphasis is to stimulate continuous innovation in education and publish the results to the outside world.

Fortin of Skoltech showed the documents where the change in career path development had been approved in 2017. The implementation in the academic culture is just starting: they are currently going through the first promotion cases. Commitment in teaching and proven involvement in educational innovation are a requirement to achieve tenure. All Assistant Professors have to write an impact statement that describes their personal impact on education and innovation. For a promotion to Associate Professor criteria of refereed publications in educational conferences and journals have to be met, together with validated contributions to educational conferences and initiatives that demonstrate proven leadership and impact on university education at national and international level, which is also the Level 4 of the career framework.

Not all universities are equally enthusiastic about this Career Framework for University Teaching. For instance TU Delft has been reluctant so far to adopt it and has been discussing since 2014 how to invent a career progression framework for university teaching that optimally matches the “unique Delft” academic culture. Meanwhile educational achievements remain highly undervalued in the Delft career promotions and, as a direct consequence, the continual professionalisation for teaching staff has more or less come to a standstill, as already described in a my September post about the disposable fulltime lecturers.

Three out of 4TU.CEE

On the second day of the gathering at Skoltech we welcomed TU Eindhoven as a new member of the CDIO community. After TU Delft (member since 2011) and University Twente (2017), now three out of the four universities of the 4TU.Centre for Engineering Education are a member. Together with The Hague University of Applied Sciences, the Dutch leave their mark on the network community! Alone together we share outcomes of applied educational research with our international partners and learn from each other’s successes and failures.

In the freezing and snowy Saturday morning most of us took the special guided tour of Moscow (private photo)

Hope and need for courage

The participants of the workshop about the Career Framework for University Teaching expressed their hope that this new career framework will soon become the new normal. Not as a lip service, but as a basis to foster education innovation and educational research. Everybody agreed that research universities will have to make deep change. The universities shall demonstrate courage in changing the rules for awarding incentives and funding dramatically. Only then they will transform the academic culture because also academics go where the money flows and conform to the awarding and funding rules, because these rules are usually based on the vision and a strategy of the institution.

We have to stop debating and have the courage to transform the system. A solid career framework that still leaves a lot of freedom to the university organisation, is at hand!